Alanson Aquante shrugged as he carefully pinched and turned fish on a large cement grill.

Alanson Aquante shrugged as he carefully pinched and turned fish on a large cement grill.

“Before we had plenty of fish here and very cheap,” he said, barely visible through the smog that filled his smokehouse in Gunjur, a fishing community on Gambia’s southwest coast.

“Now the fish is scarce I can sell it easily. The Chinese coming into the fish industry meant the price went up.”

For almost a decade Aquante, 36, has earned a living smoking small pelagic fish like sardinella and bongato be traded in local markets.

A male fish smoker in a trade traditionally dominated by women – he is one of few people profiting from the Chinese fishmeal producers in the country.

Once abundant, fish stocks in West Africa are being depleted by foreign fishermen trawling the ocean for high value species like tuna.

The unregulated and illegal industry costs West Africa US$2.3 billion annually, according to a study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, and is depriving Gambia of around 2,000 tonnes of fish a year.

Now fishmeal factories on the coast are targeting cheaper, local fish.

The factories produce small pelagic fish that are turned into animal feed and sold in Europe and Asia.

This is fuelling a booming fish farming industry worth about US$163 billion in 2015, according to the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO).

It has driven up the price, Aquante said, and fish processors – just some of the 200,000 workers in the fisheries sector – are left with scant earnings. But Aquante has a connection to buyers inland where there is less access and he can make “good money”.

“Tourism and fish provide employment to our youths,” said former minister Amadou Scattred Janneh, who is not pleased about the industry.

Janneh led efforts in March to remove a pipe belonging to Golden Lead, a Chinese-run fishmeal producer that villagers said was pumping waste into the ocean.

“Tourist operators in the area report that clients complain about the smell coming from the factories, and that it’s unsafe to swim in the waters that the factories dump their waste,” he said.

Janneh is one of many several former officials who were living in exile but have returned and are trying to expose problems with the factories, which began operating in 2016.

They raise money on social media to pay the legal fees for protesters who get arrested.

The campaign is part of a growing movement by returnees to help rebuild the country. They write letters to campaigners in communities they have established across the US and Europe.

Having helped remove a dictator from afar, they now act as watchdogs for local investments.

“I felt I had to get involved,” said Janneh, who returned a day after autocratic leader Yahya Jammeh fled the country in 2017.

“The community decided to file a lawsuit [against Golden Lead]. The case has been dragging on for almost a year and no progress.”

Janneh was born in Gunjur and became Jammeh’s information minister. In 2011, however he was sentenced to life imprisonment for distributing T-shirts calling an “end to dictatorship”.

He served 15 months – mainly in solitary confinement – before he was exiled to the US.

In August, two factories in Sanyang and Kartong were closed temporarily because of pollution, due in part to Janneh and his activists. But in Gunjur, campaigners are still active, having failed to shut down fishmeal operations there.

Tabitha Grace Mallory, a fisheries expert and head of the consulting firm China Ocean Institute, said that aquaculture has skyrocketed over the last 35 years to make up 75 per cent of Chinese seafood production.

“A lot of those fish need to be fed with fishmeal using other types of fish and because Chinese domestic waters are overfished they are trying to source much of that outside of China,” she said.

“But the actions of private companies can often be at odds with stated sustainability policies and concerns about China’s reputation abroad.”

Gambians can now voice their concerns about community investments, something that was impossible under Jammeh, said Sait Matty Jaw, a returnee from Norway who runs Gambia Watch.

Jaw, a political science lecturer at the University of the Gambia, was arrested by the notorious National Intelligence Agency for conducting a human rights survey.

“The factory in Gunjur came during the time when Gambia was really under dictatorship and people could not say anything,” he said.

“But now all these issues that are of concern, people are voicing them and they are protesting.”

It is not just fisheries that the returnees are keeping a close eye on. As officials prepare to pick a contractor to renovate the capital’s port, campaigners object to Beijing’s state-owned China Communications Construction Company being a potential candidate.

“What happened in Sri Lanka is creating a lot of fear with people, that we are going to spend a lot of money at the end of the day,” Jaw said referring to Hambantota port, which Colombo in December 2017 leased to a Chinese state-owned company for 99 years.

“Since independence, the Gambia port has been the gateway to West Africa.”

Gambia, Africa’s smallest nation and one of its poorest, is eagerly pursuing foreign investment to tackle debt that is 130 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP).

About 80 per cent of Gambia’s exports are re-exports to the more than 300 million consumers in the ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) and most are handled by the port.

The rising tensions may not bode well for China-Africa relations.

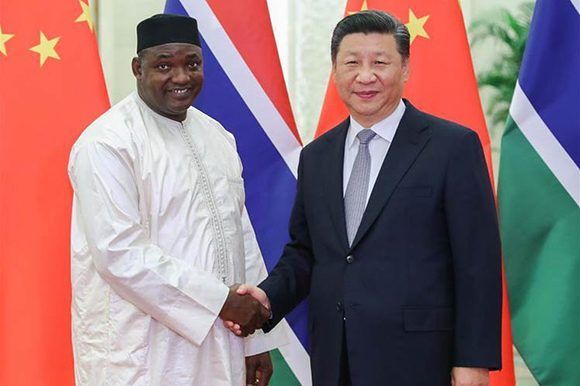

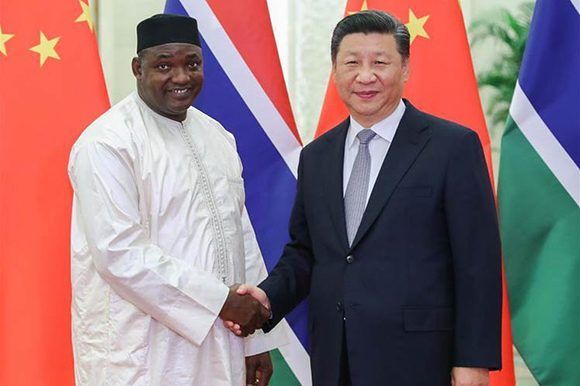

President Xi Jinping welcomed Gambian President Adama Barrow to the seventh Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Beijing in early September – the first time the country had sent anyone.

That came after China and Gambia resumed diplomatic relations in 2016 after a two-decade freeze after the African nation ditched ties with Taiwan.

At the forum, Barrow signed up to China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” buoyed by the promise of a US$44 million development grant, and US$4 million for Gambia’s military. Last year Beijing cancelled US$14 million debt accrued during the 1980s.

East of the capital in the country’s Upper River Region, China is building two major bridges which will be ready next year. Other deals include a US$50 million conference centre, which has sparked protests, and broadband infrastructure paid for by a US$25 million loan from China’s state-owned Exim Bank.

“There has not been any dialogue between investors and the community or even government,” Jaw said, adding that the new-found activism extends beyond foreign investments.

“In Faraba, where three people were shot by police, the investment was local.”

Often the resistance is against environmental destruction or a lack of information.

“Since the fishmeal plants opened there have been no audit on their operations, production capacity or biomass of the particular stock being targeted,” said Dawda Saine, a marine biologist who heads Gambia’s Artisanal Fisheries Development Agency.

FAO data suggests bonga is overfished, with a slump of almost 40 per cent between 2013 and 2014.

Although fish catch figures for the three main landing sites were not available for 2016 or 2017, the “catch has dwindled”, said Alagie Sillah, executive secretary of the Association of Gambian Fishing Companies.

“The best way to create local jobs is to set up processing plants,” he said, since they can generate onshore work.

Gambia’s National Assembly began an inquiry in July into key investment protest hotspots including fishmeal factories, but authorities need to act quickly to avoid further unrest, said human rights activist and journalist Mustapha Manneh.

“Any investment in the Gambia has to be environmentally friendly and there is no sustainable way of producing fishmeal,” said Manneh, who returned from exile in Cyprus in March 2017.

Manneh fled Jammeh’s rule after his father and brother were arrested. He has led protests against fishmeal producer JXYG in the coastal town of Kartong since arriving home – even travelling to neighbouring Senegal to speak about the issue.

For fish seller Aquante however, “life is easier” with Chinese firms around.

“The Chinese factory attracts a lot of boats to come into land and if the Chinese cannot buy all the fish, [fishermen] have to sell it to us.”

Source: https://www.scmp.com/news/world/africa/article/2164352/gambias-tolerance-chinese-fish-factories-tested-beijing-courts

Alanson Aquante shrugged as he carefully pinched and turned fish on a large cement grill.

Alanson Aquante shrugged as he carefully pinched and turned fish on a large cement grill.

![China continues to violate sustainable fishing practices in Africa Mbour, Senegal, where fishing is traditionally a small-scale business. [Sebastián Losada_Flickr]](https://fcwc-fish.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Senegal_fishing_Africa_CREDITSebastian-Losada_Flickr-800x450.jpg)